Creative Spotlight: Mozart

Read more about the life and work of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

Introduction

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) is regarded as one of the greatest composers in Western musical history. Born in Salzburg, Mozart is known for the brilliance of his compositions in all the musical forms of his time. His mature operas, The Marriage of Figaro, Don Giovanni, Così fan tutte and The Magic Flute are recognised for their wit, humour and beauty. Read on to find out more about the life and works of this world-famous composer.

Quick Facts

What Is Mozart Famous For?

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart is best known for his many compositions, written during the classical era. His best-known works range from symphonies (in particular, Symphonies no. 40 and 41 – the ‘Jupiter’); chamber works (e.g. the String Serenade no. 13 ‘Eine Kleine Nachtmusik’ (A Little Night Music) and the Gran partita serenade no. 10 for eight wind instruments); choral works (e.g. the Requiem in D minor), and his operas (including The Marriage of Figaro, Don Giovanni, Così fan tutte and The Magic Flute). His other popular works include the Piano Concerto no. 21 in C major, the Violin Concerto no. 5 in A major, the Clarinet Concerto in A major, as well as the Concerto for Flute and Harp in C major. He was also famous for being a child prodigy.

How Old Was Mozart When He Began Composing Music?

Mozart was a child prodigy. According to popular anecdote, he composed his first large-scale work (a concerto) at the age of 6. Soon after he began performing to royalty across Europe. A virtuoso violinist and keyboardist, he frequently performed alongside his sister, Maria Anna (nicknamed 'Nannerl'), who was also musically gifted. The siblings were managed by Mozart’s musician father, Leopold Mozart, who oversaw a demanding schedule of international travel and public exposure for his young children.

How Many Symphonies Did Mozart Write?

Mozart officially wrote 41 symphonies. The most famous of these is the Symphony number 40. Other famous Mozart symphonies include the ‘Jupiter’ (no. 41), the ‘Paris’ (no. 31) and the ‘Prague’ (no. 38) symphonies.

How did Mozart die?

Despite his fame and success as a composer and performer, in 1791 Mozart died at the age of 35 in significant debt. Much speculation surrounds the cause of death, with musicologists arguing that the doom-laden atmosphere of Mozart's final composition, the Requiem Mass, suggests he knew he was going to die. He was buried in a ‘common grave’ (the term for a non-aristocratic grave, not to be confused with a pauper’s grave, as is often mistakenly assumed) in the St. Marx Cemetery outside Vienna. There, in 1859, a monument was built in Mozart’s honour, although the precise location of his body remains unknown today. That memorial was later transferred to Vienna’s central cemetery, in a section dedicated to the city’s musicians.

To find exclusive Mozart DVDs, souvenirs and gifts: explore the Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart collection at the Royal Ballet and Opera Shop.

List of Operas

- Apollo et Hyacinthus (Apollo and Hyacinth) 1767

- Bastien und Bastienne (Bastien and Bastienne) 1768

- La finta semplice (The feigned simpleton) 1768

- Mitridate, Re di Ponto (Mithridates, King of Pontus) 1770

- Ascanio in Alba (Ascanius in Alba) 1771

- Il sogno di Scipione (Scipio's Dream) 1772

- Lucio Silla 1772

- La finta giardiniera (The pretend garden-maid) 1775

- Il re pastore (The Shepherd King) 1775

- Thamos, König in Ägypten (Thamos, King of Egypt) incidental music 1773-90

- Idomeneo, re di Creta (Idomeneus, King of Crete) 1781

- Die Entführung aus dem Serail (The Abduction from the Seraglio) 1782

- Der Schauspieldirektor (The Impresario) 1786

- Le nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro) 1786

- Don Giovanni 1787

- Così fan tutte (All women are like that) 1790

- La clemenza di Tito (The clemency of Titus) 1791

- Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute) 1791

Gallery

Early Life

Mozart was born in Salzburg in 1756, the youngest child of Leopold Mozart, a violinist and composer, and his wife, Anna Maria. A child prodigy, from 1762-73 he toured Europe with his sister, Maria Anna (or 'Nannerl'), performing in royal and aristocratic courts under his father's management. His earliest opera compositions date from this era, including the Bastien und Bastienne (1768, a Singspiel) and La finta semplice (The Feigned Simpleton), an opera buffa, or comic opera.

A musical childhood

On January 27 1756, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was born in Salzburg, Austria. His father, Leopold Mozart, was a musician who worked as a composer and violinist for the archbishop of Salzburg. His mother, Anna Maria, supported the musical education of their two children. She gave birth to seven children in total, but only Wolfgang and his older sister survived to adulthood. Mozart’s musical talents were apparent from a remarkably early age: by the age of 3, he could play chords on the harpsicord by ear, by 4 he could play short pieces, and by 5, he was composing his own works. By the age of 6, he was a budding composer and skilled keyboardist. In 1762, Leopold brought his son to the imperial court in Vienna, and from the following year, Wolfgang and his sister, Maria Anna (known as Nannerl), embarked on exhaustive tours of Europe as musical prodigies.

Touring as a prodigy 1763-67

Under the guidance and management of Leopold Mozart, Wolfgang and Nannerl travelled across Europe, performing for royalty in Paris and London, as well as all the main musical centres of Europe: Munich, Frankfurt, Brussels, Stuttgart, and others. While in London, Mozart’s musical gifts attracted the attention of Johann Christian Bach (the youngest son of the composer, Johann Sebastian Bach), who was a major influence on Mozart’s earliest symphonies. The experience of travelling exposed Wolfgang to a variety of musical styles at an early age, and it also contributed to his fluency in a variety of European languages. However, the pressures were intense. Leopold Mozart described his son as ‘The miracle which God let be born in Salzburg’, and as he grew older, Wolfgang struggled to free himself from his father’s controlling influence.

Early successes and positions: Vienna and Salzburg

The young Wolfgang wrote his first secular music drama, Apollo et Hyacinthus, at the tender age of 11 in 1767. It was a commission for the Benedictine University in Salzburg where Mozart’s father was heavily involved in the musical scene. The Mozarts moved to Vienna in 1767, where Mozart wrote Bastien und Bastienne, a one-act singspiel (a dramatic play with songs), and La finta semplice (The Feigned Simpleton, 1768), an Italian-language opera buffa (comic opera), which was performed in the palace of the Archbishop in Salzburg the following year. In October 1769, Mozart was appointed Honorary Konzertmeister at the court in Salzburg.

Three Italian tours

In December 1769, Leopold took his son on an intensive 15-month tour across Italy, where, alongside extensive performances, Wolfgang continued his musical studies with the goal of mastering the Italian operatic style: a prerequisite for any successful composer. In early 1770, the 14-year-old Mozart was commissioned to write an opera for the opening of Milan’s winter carnival season. That opera, Mitridate, re di Ponto (Mithridates, King of Pontus), would become Mozart’s first successful opera seria when it was performed in December that year. Also in 1770, Mozart travelled to the Sistine Chapel in Rome where, according to popular legend, he heard Allegri’s Miserere, a supposedly ‘unpublished’ choral work shrouded in secrecy, and transcribed it by ear in its entirety. Three months later, Mozart was summoned back to Rome for an audience with the Pope, who later awarded the young Wolfgang the Chivalric Order of the Golden Spur for his musical achievements.

A further Italian tour followed in 1771. In October that year, Mozart’s opera, Ascanio in Alba, received its premiere in Milan as part of the wedding celebrations of the Archduke Ferdinand and Princess Beatrice of Modena. Father and son remained in Milan, hopeful that the opera’s success would lead to a royal appointment, or a royal patronage for the young Mozart in one of the Habsburg courts – but the Empress Maria Theresa refused Leopold’s requests.

The third and final Italian tour spanned October 1772 – March 1773, during which time, Mozart’s latest opera, Lucio Silla, triumphed despite a challenging, 6-hour premiere in December 1772. It ran for 26 performances. A variety of chamber works, including string quartets, motets and divertimentos also date from this period.

The return to Vienna

Wolfgang’s return to Vienna in 1773 saw the maturation of his compositional craft, with symphonies including the ‘Little’ in G minor, his first piano concerto, more symphonies, concerti, sacred works and serenades. His opera buffa, La finta giardiniera (The pretend garden-maid) enjoyed a successful premiere in Munich in 1774.

Salzburg

From 1775-77, he held the salaried position of Konzertmeister (court musician) in the court of Prince-Archbishop Hieronymus Colloredo, during which time Mozart composed the opera seria/dramatic cantata, Il re pastore (The Shepherd King), as well as sacred and instrumental works. These included some five violin concertos and three piano concertos, as well as (confusingly) a concerto for three pianos. By 1777, he had become increasingly interested in writing works for the opera stage, and he resigned his position. At 21 years of age, Wolfgang set out in search of new opportunities.

Further Travels

In 1777 Mozart travelled with his father to Munich, Augsburg and Mannheim in search of a position at court, without success. In Mannheim, Mozart fell in love with the soprano, Aloysia Weber, the second of four sisters, but when his father learned of their plans to travel to Italy, Leopold intervened, instead dispatching his son to Paris, where in 1778, he was joined by his mother. Mozart’s D-major symphony, the Concert Spirituel, was a great success with Parisian audiences, but Mozart got into debt, and the trip took a tragic turn when his mother’s health declined, and in July 1778 she died. Grieving in Paris, Mozart stayed with his friend, Friedrich Melchior, Baron von Grimm, who confided in Leopold that Mozart’s prospects looked unfavourable. Although Mozart was later offered a position in Paris, he declined it, and returned home to Salzburg in mid-January 1780, where his father had negotiated him a position as court organist.

Back to Salzburg and Munich

Mozart’s return home saw a flurry of creative activity. His most popular works from this time include: the Sinfonia Concertante for violin and viola, the Coronation Mass, and Zaide, another Singspiel. In Summer 1780, he received an opera commission from the opera theatre in Munich, which became Idomeneo, re di Creta. The opera had its premiere in 1781, soon after Mozart’s 25th birthday, and it was a success.

Vienna again – and an argument with the archbishop

Following the success of Idomeneo, Mozart was summoned to Vienna to serve the Archbishop Colloredo. Unfortunately, the relationship soon soured: the archbishop housed Mozart in humble lodgings and banned him from playing at lucrative concerts. Tensions between the two men came to a head and Mozart resigned from his position in a stormy meeting in 1781. Mozart remained in the city, lodging with the family of his former girlfriend, Aloysia Weber (who was herself now married to a court painter and actor). He earned a living teaching, writing music for publication (including the ‘Gran Partita’ Wind Serenade in 1781), and playing in concerts.

'Very many notes, my dear Mozart’

Having begun work on his first full-length German-language opera, Die Entführung aus dem Serail (The Abduction from the Seraglio) in 1771, the premiere took place at the Vienna Burgtheater in July 1782. According to legend, the Emperor reacted, saying, ‘Very many notes, my dear Mozart’. While the story may be a fiction, it is true that the opera is more densely scored than his earlier works, with rich textures, ornamentation of vocal lines, and longer, more complex arias. Although the opera was received favourably, it didn’t generate huge income for the composer, and so he turned to other compositional forms, including piano concerti and a set of six string quartets inspired by the works of Joseph Haydn. Other inspirations included Bach and Handel (see our Handel Creative Spotlight here). Mozart’s Mass in C minor was left incomplete, but the ‘Kyrie’ and ‘Gloria’ from this work show his indebtedness to the Baroque tradition, with its sparse textures and vocal lines. Other popular works from this era including the 1782 ‘Haffner’ symphony, and the ‘Linz’ Symphony no. 36 in C major.

A prolific composer

Throughout the 1780s Mozart continued to perform as a keyboard soloist, giving the premieres of his piano concerti (of which he wrote a total of 12 between 1782-91) to great acclaim. During this time his mastery of orchestration developed hugely, demonstrated by the symphonic unity of the later piano concerti, and their dramatic interactions between the soloist and the orchestra. There was also an outpouring of chamber music, including sonatas for piano and violin, a quintet for piano and wind instruments, and more string quartets. In 1785, the composer Joseph Haydn remarked to Leopold Mozart: ‘Your son is the greatest composer known to me in person or by name’.

Money troubles – and Salieri

Mozart and his wife, Constanze, had lavish tastes and often lived beyond their means, despite Mozart’s success as a pianist and composer. In the Vienna Court, Kapellmeister Antonio Salieri wielded considerable influence, in accordance with the fashion for Italian music. While the two men were on friendly terms (unlike the bitter rivalry depicted in Peter Shaffer’s 1979 play, Amadeus, made famous in the 1984 film), Mozart realised it made more sense for him to turn his attentions to the Vienna Court Opera of Joseph II.

The Marriage of Figaro: the first Da Ponte opera

When Mozart became acquainted with Lorenzo Da Ponte, an Italian-Jewish abbé-adventurer with a colourful history of his own, creative sparks immediately flew. At Mozart’s suggestion, Da Ponte wrote a libretto based on Beaumarchais’ comedy, Le Mariage de Figaro. Mozart’s opera, Le nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro), depicts a young engaged couple, Susanna and Figaro, who work in the household of the Count Almaviva. On the night before their wedding, the Count attempts to invoke an ancient feudal right, according to which he can sleep with the bride. A series of chaotic events ensue, as the young lovers attempt to outwit the Count, joining forces with his heartbroken wife, the Countess, to plot their revenge.

The comedy, the nuanced characterisation, the ensembles and arias all combined to create a work of sublime beauty and depth. The opera was warmly received at its Vienna premiere in May 1786, but it wasn’t until the work was performed in Prague that it received a truly rapturous reception. In 1787 the Bohemian capital hosted the premiere of Mozart’s new symphony, the ‘Prague’; a work which showcased the talents of the city’s skilled musicians.

An encounter with the young Beethoven

In May 1787, Mozart’s father, Leopold died. Wolfgang continued to compose, creating string quartets and other chamber works of increasing sophistication, including the now-famous Eine kleine Nachtmusik (A Little Night Music). The 17-year-old Ludwig van Beethoven was in Vienna at the time and, according to anecdote, he met Mozart, his idol at the time. The legend goes that Ludwig played one of his own works for Mozart, who remarked to his wife, ‘Watch out for that boy. One day he will give the world something to talk about’. Mozart agreed to teach him, but it wasn’t to be: Beethoven was summoned back to his hometown of Bonn, where his mother was seriously ill, putting an end to those plans.

Don Giovanni

In 1787, Mozart began work on his second opera with Da Ponte, Don Giovanni. Based on the ancient Spanish legend of Don Juan, the opera tells the story of Don Giovanni, a prodigious womaniser whose sinful past catches up with him in a dramatic encounter with a supernatural statue over dinner. The work, like Figaro, is regarded as a masterpiece, showcasing Mozart’s skill at conjuring dramatic contrasts (the Overture powerfully evokes the flames of hell, in a nod to the opera’s climactic, supernatural ending), as well as Leporello’s popular Catalogue aria, and a host of heart-rending solos and duets.

The opera was completed on 28 October 1787, the night before the Prague premiere, and was, like Figaro, rapturously received. Two new arias were added for the Vienna premiere in May 1788, by which time Mozart had been appointed as ‘chamber composer’ to Emperor Joseph II. In this part-time role, Mozart was commissioned to compose dances for the annual ball held in the palace’s ornate Redoutensaal ballroom.

Final years

By 1788, Mozart’s financial situation had worsened. This was in part due to the Austro-Turkish War, which caused finances across the city to become more straitened, with a knock-on effect on the aristocracy’s patronage of the arts. During this time, Mozart composed his two most famous symphonies, nos. 40 and 41, the ‘Jupiter’ (1788), but he was forced to borrow from his friends. He embarked on journeys to Leipzig, Dresden and Berlin (1789), Frankfurt, Mannheim and elsewhere in Germany (1790) in the hope of improving his prospects. Letters from this time demonstrate Mozart’s low mood, and some commentators have suggested that he was suffering from depression.

The final Da Ponte opera: Così fan tutte

Despite the stress of his situation, Mozart continued to compose, albeit at a slightly slower rate. Mozart’s final collaboration with Da Ponte, Così fan tutte (All Women are Like That), was an Italian-language comic opera first performed at the Vienna Burgtheater in 1790.

In the opera, the lives of two young couples are plunged into turmoil when, following an ill-advised bet, two young husbands-to-be, Ferrando and Guglielmo, disguise themselves and swap girlfriends in an attempt to prove the fidelity of their fiancées. The opera enjoyed five performances before the run was interrupted by the death of Emperor Joseph II. After the official period of mourning had ended, five further performances were given.

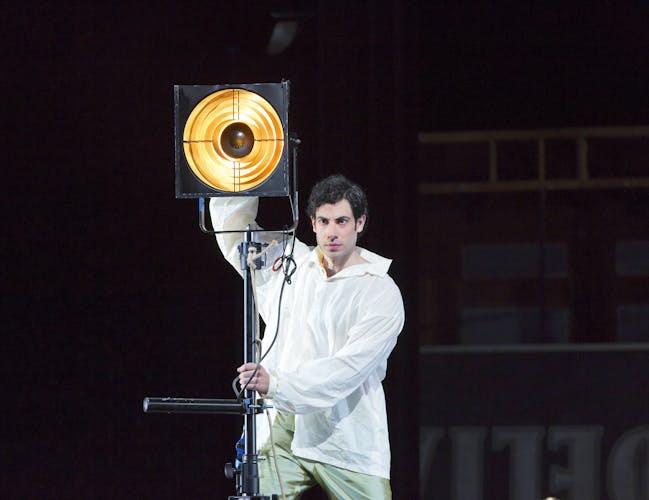

Final opera: The Magic Flute

Mozart’s final opera, Die Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute), was composed in 1791, the same year in which his Clarinet Concerto was first performed. The Magic Flute had its premiere not in an aristocratic court theatre, but in the Theater auf der Wieden, a popular theatre in the suburbs of Vienna. The opera tells the tale of Tamino, a young Prince, who falls in love with the captured Princess Pamina, and vows to rescue her on the orders of her mother, The Queen of the Night.

Accompanied by his sidekick, the bird-catcher Papageno, the two men set out in search of true love, with Tamino entering a mysterious brotherhood of men, and undergoing a series of trials before he and Pamina are freed. To Papageno’s delight, he meets the woman of his dreams, Papagena, in a lively finale where they share their excitement at their future plans of starting a big family together. The opera was a huge success, starring the actor-singer (and theatre manager) Emanuel Schikaneder, with huge crowds flocking to see the Mozart’s latest work.

Musical style

Mozart’s musical style is in many ways the epitome of classical music. There is grace, elegance and balance to his music, and the transparency of the texture allows the listener to appreciate the sophisticated harmony and counterpoint. Mozart is also famed for the prolific quantity of his compositions, which span a wide range of musical forms. He excelled in chamber works, such as solo sonatas, string quartets and wind serenades, as well as large-scale works, including oratorios, sacred choral music, symphonies, concerts and operas. He is widely seen as evolving all of these forms, and his influence on the world of opera is profound.

Freemasonry

Like many men in Viennese society, Mozart was a member of the Freemasons: a secretive, all-male society in which many of the city’s most influential individuals were active. He joined in 1784 and remained a member until his death in 1791. According to legend, Mozart’s final opera, The Magic Flute (1791) caused upset among some masons because of its reflection of secret ceremonies and rites. There are elements of masonic imagery dotted throughout the opera, such as the mysterious Brotherhood of Men to which the character, Sarastro, belongs, and which Tamino enters. The opera’s numerical symbolism – with references to the number ‘3’ in the Overture, three-part harmonies, as well as the presence of the Three Ladies and Three Boys – is arguably a nod to the Masonic movement. References to Enlightenment philosophy in the opera – with its warring forces of light and dark – are also present in certain branches of freemasonry.

Personal life

Mozart’s relationship with his father was complicated. While he was indebted to his father for his early musical education, and the management of his career as a child prodigy, Leopold had a tendency to be domineering, and Mozart struggled at times to assert his independence in adulthood. As a child, Mozart was close to his sister, Nannerl, but their paths diverged when, at the age of 18, Leopold deemed Nannerl’s education complete, while Mozart embarked on a series of international tours.

In 1777, Mozart stayed in Mannheim with the Webers, a musical family. He fell in love with the second-eldest daughter, Aloysia, but when Mozart later returned to Mannheim, she was no longer interested in him. By 1781, Aloysia had married the court musician Joseph Lange, and Mozart lodged with them in Vienna. That year he fell in love with Constanze Weber (Aloysia’s younger sister), and in December 1781, he asked for his father’s blessing for their union. When Leopold refused, the couple moved in together, creating a scandal. They eventually married in August 1782, the day before Leopold’s consenting letter arrived. They had six children, only two of whom survived infancy: Karl Thomas, and Franz Xaver Wolfgang Mozart.

Mozart’s sense of humour, like much of his up-beat music, was lively and mischievous. He also took a childlike delight in scatological jokes and bad language, and many of his surviving letters contain rude words and vulgar puns. In Peter Shaffer’s 1979 play, Amadeus, rival composer Salieri laments the gulf between the divine genius of Mozart’s music, and the crudeness of his character. The play inspired the 1984 film of the same name directed by Miloš Forman and starring Tom Hulce in the titular role. In 2025, Sky Arts released a limited-series, also inspired by Shaffer's play, by acclaimed writer, Joe Barton. The series stars Will Sharpe as Mozart and Paul Bettany as Salieri.

Death and Legacy

Mozart’s health declined in early September 1791. At the time, he was in Prague for the premiere of his penultimate opera, La Clemenza di Tito (The Clemency of Titus). Despite this, he conducted the Vienna premiere of The Magic Flute on 30 September 1791. In November, his condition deteriorated, and although he was bedridden with a fever, he was still occupied with completing his final composition, the Requiem Mass. He died on 5 December 1791, at the age of 35. Although his funeral was a humble affair, there were memorial services and concerts given in his honour in Vienna and Prague. Soon after his death, biographers set to work, documenting his extraordinary life and works, and his legacy, as a musical innovator of sublime genius, lives on.

Rumours of a Salieri conspiracy

Within a decade of Mozart’s death, rumours had begun to circulate that Mozart’s ‘rival’ court composer, Antonio Salieri, had poisoned Mozart out of jealousy. These rumours had no basis in fact, but when in 1823, Salieri suffered a mental breakdown, he accused himself of killing Mozart. Before his death in 1825, Salieri defended himself, saying in a moment of lucidity: ‘There is no truth to the absurd rumour that I poisoned Mozart.’ However, the damage was done. The story took on a life of its own and immortalised by the great Russian poet, Alexander Pushkin, in his miniature tragedy, Mozart and Salieri, published in 1830. Some 150 years later in 1979, the playwright Peter Shaffer published his play, Amadeus, depicting Salieri as an embittered musical rival, driven to murder by Wolfgang’s childlike, profane humour.

In Pop Culture

Mozart’s music has been included in innumerable films and TV shows, including:

- The Ave Verum Corpus in L'Age d'Or (1930)

- The ‘Jupiter’ Symphony in Annie Hall (1977)

There are also many biopics, films and plays about Mozart. The most famous of these is the film Amadeus (1984), based on Peter Shaffer’s 1979 play. The film was directed by Miloš Forman, and starred F. Murray Abraham (Salieri) and Tom Hulce (Mozart), and won eight academy awards.

Watch more

- Main Stage

The Magic Flute

- Opera and Music

Mozart's masterpiece – an enchanting quest for love and wisdom.

- Main Stage

The Marriage of Figaro

- Opera and Music

It’s Figaro’s wedding, and you’re invited to join the Almaviva household for an uproarious day of revelation and scandal.

Watch on Stream

Mozart’s classic opera puts love under the microscope with comic and disturbing results.