Faust Musical Highlight

Read more about the music of Faust and the giddy exuberance of the waltz.

Faust Musical Highlight: The Giddy Exuberance of the Waltz

Gounod’s opera Faust is full of really memorable tunes, especially for the chorus. One of the most delightfully exuberant comes towards the end of Act II – ‘Ainsi que la brisé légère’. It has a lightness and consistent propulsion that captures the spirit of the words, which describe waltzing as just like a light breeze raising dust from fields. The first verse describes being drawn into the waltz and making the countryside resound with singing. In a second verse, the words are of dancing till out of breath, until carried away as the earth dizzily spins round.

The final lines are: ‘Quel bruit! Quelle joie dans tous les yeux!’ – 'What a noise, what happiness in everyone’s eyes!' By the middle of the 19th century, Europe whirled to the waltz. For people with two legs and a left/right two-time rhythm, the effect of three beats in a bar proved intoxicating. It invited a sense of perpetual motion through the momentum of turning as you dance. And with this came associations of liveliness, levity and even lasciviousness – you need to hold your partner very close! The waltz was the dance of hedonistic enjoyment.

So when Gounod uses a waltz to introduce the celebrating crowds in Act II of Faust, he signals through his musical setting their complete happiness. Gounod uses more than the three-beats-in-the-bar regularity of the waltz rhythm and the steady oom-pah-pah accompaniment. The genius is in a melody that has a sense of lift to it in the way that the high notes are thrown into relief. While the first part of the waltz begins with repeated notes in a middle register, the second section picks out a high note at the beginning of each phrase (echoed in the orchestration straight after).

This creates that sense of lift, as though the tune just can’t be kept down. Using the waltz as a social dance that evokes a sensation of group abandonment to pleasure occurs regularly in operas and operettas. For example, Puccini uses it in La rondine with a series of waltz sections that sweep through Bullier’s dance hall, where Act II is set. But it works for solo moments too. One of the highlights of Gounod’s Faust is Marguerite's Jewel Song.

She discovers a box of wonderful jewels, conjured up by Méphistophélès to help Faust seduce her. As she opens the box, then tries the diamonds and pearls on, she sings an aria famous for its coloratura (fast and delicate high notes). Here is the same musical creation of breathless excitement, the racing heart. It shows itself in the main tune, which begins with a run up to one little high note – a thrill of delight – followed by a phrase of incredulous delight, and continues through successive rising phrases. Gounod recognized a good bit of musical characterization and used exactly the same technique in his opera Roméo et Juliette.

In the first act, Juliette declares she has no intention of marrying and settling down to some domestic restraint. Instead, 'Je veux vivre' – she wants to live! She sings about this in a gloriously catchy coloratura waltz song that is sister to Marguerite’s Jewel Song.

The little gasping effect is now the breathless enthusiasm of Juliet as the song starts – her will to indulge in life’s experiences is already in the audience’s mind contrasted with the knowledge of how doomed a desire this is. And of course, in Faust, we also know that Marguerite’s happiness will be short-lived but while that waltz song plays, we forget the future and just give in to the moment and that delightful, invigorating, seemingly endless whirl.

Watch Now

Watch on Stream

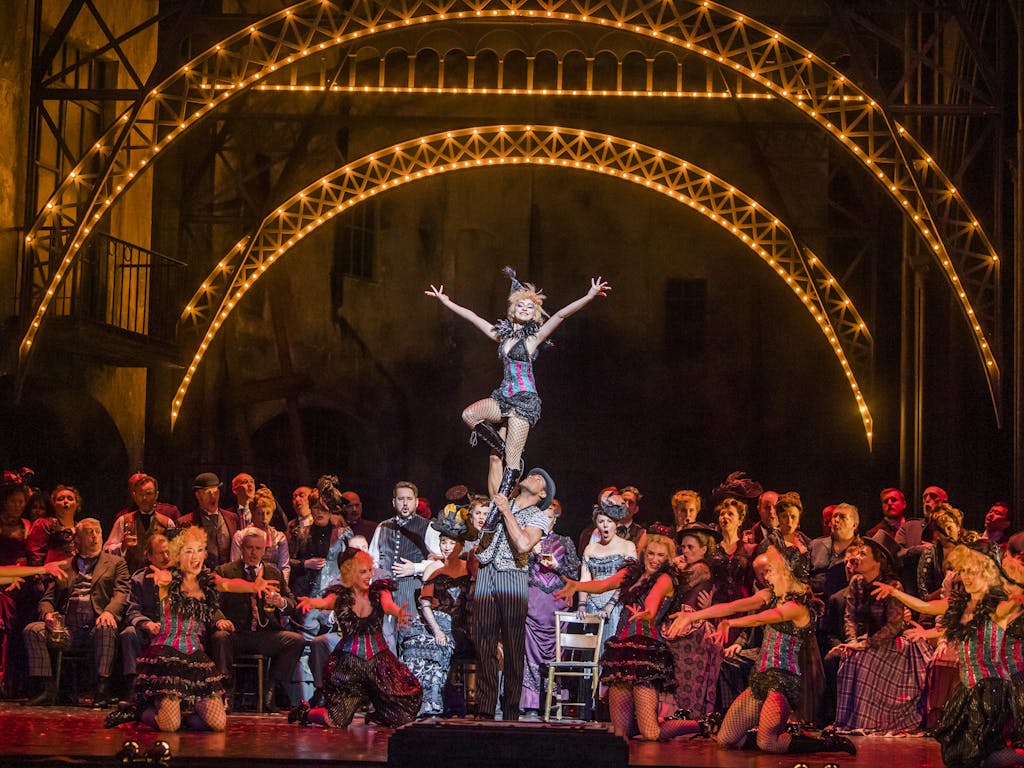

A deal with the devil. What could go wrong? Experience the decadence and elegance of David McVicar’s spectacular production of Gounod’s masterpiece.