Opera Essentials: Ring Cycle

A quick guide to Richard Wagner’s Ring cycle, consisting of four operas: Das Rheingold, Die Walküre, Siegfried and Götterdämmerung.

Richard Wagner’s Ring cycle (Der Ring des Nibelungen – The Ring of the Nibelung) is one of the most epic, all-consuming and extraordinary operatic experiences. The cycle is a tetralogy, consisting of four operas: Das Rheingold, Die Walküre, Siegfried and Götterdämmerung. Composed over a 26-year period between 1848 and 1874, the operas total 15 hours in duration, and as a whole they constitute a monumental musical achievement, with enormous cultural influence. Read on to find out more about the cycle in our guide to Wagner’s Ring. For more information about the life and other works of Richard Wagner, go to our Creative Spotlight feature.

Quick Facts

Answering some of the most asked questions about the Ring cycle.

Who wrote the Ring Cycle?

Richard Wagner (1813-1883) wrote the Ring cycle. He composed the libretti (or text) for each opera in reverse chronological order, starting with the text for Götterdämmerung, and ending with the text (or ‘poem’, as Wagner called it) for Das Rheingold. He then proceeded to compose the score sequentially, starting with Das Rheingold, followed by Die Walküre, Siegfried and lastly Götterdämmerung.

How long is the Ring Cycle?

If played continuously back-to-back, the four operas in Der Ring des Nibelungen would last 15 hours in duration. Das Rheingold is the shortest opera in the cycle, lasting approximately 2 ½ hours without interval. Exclusive of intervals, the music of Die Walküre lasts approximately 5 hours, Siegfried lasts just over 4 hours, and Götterdämmerung lasts approximately 4 ½ hours. Performances of Die Walküre, Siegfried and Götterdämmerung are usually performed with two intervals each, and complete performances of the Ring cycle usually unfold over a minimum of four consecutive days. It is the ultimate artistic and logistical undertaking for any opera company.

How many operas are in the Ring Cycle?

The Ring cycle consists of four operas, the first of which (Das Rheingold – The Rheingold) Wagner described as a Vorabend (preliminary evening), setting the main events of the rest of the cycle in motion. Die Walküre, the second opera in the cycle, marks the start of the story in earnest, with Siegfried and Götterdämmerung continuing the mythic tale to its climactic conclusion.

What are the operas in the Ring Cycle ?

The four operas of Wagner’s Ring cycle are Das Rheingold (The Rheingold), Die Walküre (The Valkryie), Siegfried and Götterdämmerung (Twilight of the gods).

What are the most famous pieces from the Ring Cycle?

The most famous piece of music from the whole cycle is The Ride of the Valkyries, the galloping orchestral fanfare which opens Act III of Die Walküre. Other famous excerpts from the Ring include the Prelude to Das Rheingold, Siegfried’s Journey down the Rhine and Siegfried’s funeral music, and Brünnhilde’s immolation scene, all from Götterdämmerung.

What is the story behind the Ring Cycle?

Inspired by ancient German, Norse and Icelandic Sagas, the Ring cycle tells the mythic story of a ring of power that curses the owner, drawing gods and mortals into an epic tale of rivalry and conspiracy. Wagner was also inspired by Greek tragedy, using the orchestra as a ‘chorus’ to articulate the innermost feelings and motivations of the characters.

Story Summary

The Ring cycle tells the story of a ring that grants the bearer the power to rule the world. In the first opera, Das Rheingold, the ring is forged from gold that is stolen from a trio of Rhinemaidens by Alberich, a greedy dwarf. Alberich renounces love in order to possess the ring and its power, but when it is taken from him by Wotan, ruler of the gods, Alberich unleashes a terrible curse: anyone who possesses the ring will be murdered by its next owner. And so, the stage is set for a series of climactic events, pitting gods against mortals in a conflict spanning multiple generations...

History

The idea and the text

Richard Wagner began writing the Ring cycle in 1848. It was a time when Germany was largely under foreign occupation. Wagner, like many of his fellow countrymen, sought to embody a feeling of German national identity through the creation of a ‘national opera’ based on the ancient Nibelungenlied, a 12th-century epic poem written in High German. Wagner wrote a preliminary sketch of the story, The Nibelung Myth as Sketch for a Drama, in 1848, and by 1850, he had composed an initial musical sketch for Siegfrieds Tod (Siegfried’s Death). He realised that he required a preliminary opera, Der junge Siegfried (The Young Siegfried) in order to explain the backstory to the events of that opera, and by October 1851, the concept had expanded again. He decided that four large-scale operas were required to give the story its fullest expression and emotional power. He completed all four opera texts (written in reverse order) by December 1852.

The music

The music, by contrast, came in chronological order. He began composing the score for Das Rheingold in 1852, followed by the music for Die Walküre. He was part-way through Siegfried when, in 1857, he set the project aside for 12 years. During this time, he composed two other large-scale operas: Tristan und Isolde and Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. He didn’t return to the Ring until 1869. By this time, he was living on Lake Lucerne under the patronage of King Ludwig II, an eccentric Bavarian monarch who had developed a passion for Wagner’s mythological operas. Thanks to the financial stability provided by King Ludwig’s support, Wagner was able to put aside his money worries, and compose freely, bringing his hugely ambitious Ring cycle project to fruition.

Premieres

At the insistence of King Ludwig, ‘special previews’ of the first two operas, Das Rheingold (22 September 1869) and Die Walküre (26 June 1870) were given at the National Theatre in Munich. It was a mark of King Ludwig’s admiration for Wagner that he agreed to fund the construction of an entirely new opera theatre to house the premiere of the complete Ring cycle. That theatre, the Bayreuth Festspielhaus, opened in 1876. Its first performances consisted of the first ever complete Ring cycle, and they took place on consecutive nights between 13 to 17 August 1876.

Reception and legacy

The impact of the cycle was enormous. There was immense excitement over the cycle’s premieres, and there were reports that after hearing the Prelude of Das Rheingold, the audience shouted for Wagner for 15 minutes, while upon the conclusion of the final instalment of the cycle, the audience burst into ecstatic applause, calling for the composer until he appeared at last.

More broadly, the impact of the cycle (and of the composer’s music more generally) rippled across Europe and the rest of the world, resulting in the phenomenon known as ‘Wagnerism’. To this day, staging a Ring cycle remains the ultimate test for any opera company, and Wagner’s story, with its lavish demands, has inspired a plethora of stagings.

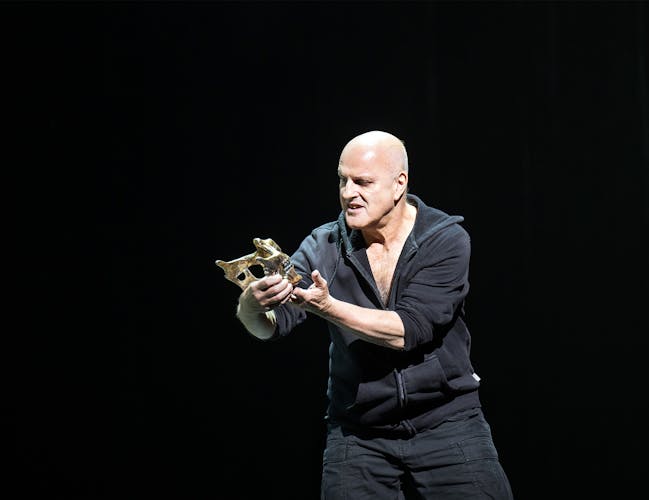

The Royal Opera’s current production, directed by Barrie Kosky, takes the vantage point of Erda, goddess of earth, as a starting point, and what the audience witnesses on stage is a journey through memory and mythology…

Music

Leitmotifs

Wagner’s Ring cycle is famed for its use of musical Leitmotifs (‘leading motifs’). The term refers to musical fragments that recur throughout the cycle, and which come to be associated with different dramatic themes at different moments. What makes the Ring cycle’s music so unique is the way in which these Leitmotifs evolve and combine with seemingly infinite variety throughout the opera, transforming their emotional impact and rewarding multiple listens.

Ironically, the term was never authorised by Wagner, who wished to avoid an overly-literal interpretation of his music. However, when the musicologist Hans von Wolzogen published his ‘guide’ or Leitfaden to the Ring 1876, the term stuck. Some of the most recognisable motifs in the cycle include the so-called ‘Fate’ motif, the Valhalla motif and Siegfried’s horn theme.

The orchestration

The Ring cycle requires an orchestra of nearly 100 players. Wagner’s music requires expansions to all sections of the orchestra, from the strings to the woodwind and brass, where additions include a number of Wagner tubas (brass instruments invented specifically for the Ring cycle). Wagner also wrote richly for the harp (6 harpists are required!), and included more unusual instruments, such as 18 on-stage anvils.

The Ride of the Valkyries

The Ride of the Valkyries is heard in the opening of Act III of Die Walküre. It is a powerful moment for the orchestra, which depicts the flight of a group of eight Valkyrie sisters through the air. Following a dramatic flourish in the strings, trilling woodwinds create a sense of weightlessness, while an upward-leaping, fragmented fanfare evokes lift-off, as well as the galloping hooves of the Valkyrie sisters’ steeds.

Das Rheingold

Originally described as a Vorabend (or preliminary evening), Das Rheingold is the first opera in the cycle. Das Rheingold introduces the central characters and arc of the cycle, featuring the ring of power, and the curse laid upon it by the greedy dwarf, Alberich, whose effects ripple down through the subsequent three operas. The cast consists entirely of gods, dwarves and other supernatural beings: there are no mortals in this chapter of the Ring.

- Wotan (bass-baritone)

- Loge (tenor)

- Fricka (dramatic mezzo-soprano)

- Freia (soprano)

- Froh (tenor)

- Donner (baritone)

- Erda (contralto)

- Nibelungs

- Alberich (baritone)

- Mime (tenor)

- Giants

- Fasolt (bass)

- Fafner (bass)

- Rhinemaidens

- Woglinde (soprano)

- Wellgunde (soprano or mezzo-soprano)

- Floßhilde (mezzo-soprano)

In the first opera, Das Rheingold, the ring is forged from gold that is stolen from a trio of Rhinemaidens by Alberich, a greedy dwarf. Alberich renounces love in order to possess the ring and its power, but when it is taken from him by Wotan, ruler of the gods, Alberich unleashes a terrible curse: anyone who possesses the ring will be murdered by its next owner. Wotan immediately sees the power of the curse in action: he offers the ring as payment to a pair of giants, Fafner and Fasolt, for constructing the palace of the gods (Valhalla). The giant-brothers immediately fight, and Fafner kills Fasolt. Erda, goddess of the Earth, warns Wotan that possession of the gold will lead to the downfall of the gods. Reluctantly, Wotan gives Fafner the ring, and leads the gods to Valhalla, their new home.

The Prelude to Das Rheingold begins with a low E-flat in the double basses. From this foundation, Wagner evokes the creation of an entire mythic universe, bubbling up through the waters of the river Rhine. The E-flat major lasts for 136 bars and is effective at creating a sense of mythic time. The opera introduces many of the cycle’s major themes, including the insistent triplet Nibelung motif and the majestic Valhalla chords.

Gallery

Die Walküre

Following on from Das Rheingold, with its cast of gods and dwarves, Die Walküre unfolds – at least to begin with – in the world of human beings, with Wotan and the question of the Rhinegold taking a background role. On a stormy night, two mortal strangers fall in love, little suspecting that their relationship will have fatal consequences, both for them – and the gods that influence their fate.

- Siegmund (tenor)

- Sieglinde (soprano)

- Hunding (bass)

- Wotan (bass-baritone)

- Fricka (dramatic mezzo-soprano)

- Brünnhilde (high dramatic soprano)

- Gerhilde (soprano)

- Ortlinde (soprano)

- Waltraute (dramatic mezzo-soprano)

- Schwertleite (contralto)

- Helmwige (soprano)

- Siegrune (mezzo-soprano)

- Grimgerde (mezzo-soprano)

- Roßweiße (mezzo-soprano)

In Die Walküre, two mortal twins, Sieglinde and Siegmund fall in love. Despite wielding the enchanted sword, Nothung, Siegmund is killed by Sieglinde’s husband, Hunding, and the blade shatters. Sieglinde is saved by Wotan’s daughter, the Valkyrie Brünnhilde. In protecting Sieglinde and her unborn child, she disobeys her father. His punishment is to take away her immortality, and to put her into an enchanted slumber from which a mortal man will wake her, and claim her has his wife. Horrified by this shameful fate, Brünnhilde pleads with Wotan, who relents and encircles her with a ring of fire, ensuring that only a hero who knows no fear can awaken her.

The music of Die Walküre is highly dramatic and memorable. Highlights include the Storm sequence in the opening scene, Siegmund’s radiant aria ‘Winterstürme wichen dem Wonnemond’ ('Winter storms gave way’), Sieglinde’s phrase ‘Oh herrstes Wunder’ (‘Oh highest wonder’ – sometimes referred to as the ‘Glorification of Brünnhilde’ theme) when she learns she is carrying Siegmund’s child, the famous Ride of the Valkyries, and Wotan’s emotional farewell to his daughter, Brünnhilde, in the final act.

Siegfried

Siegfried is the son of twins Sieglinde and Siegmund. Following the death of his mother, he has been raised by Mime, brother of Alberich, who stole the ring. Siegfried is a hero of incredible strength, but of somewhat limited intellect - yet his fearlessness becomes an indomitable weapon. Using the reforged fragments of his father’s sword, Nothung, he triumphs over the vengeful dragon Fafner, and experiences a profound awakening that leads him to defeat Wotan the Wanderer. He goes on to find love, when he awakens the sleeping Brünnhilde from her enchanted slumber.

- Siegfried (tenor)

- Mime (tenor)

- Wotan (disguised as The Wanderer) (bass-baritone)

- Alberich (baritone)

- Fafner (bass)

- Waldvogel (The Wood-bird) (coloratura soprano)

- Erda (contralto)

- Brünnhilde (high dramatic soprano)

In Siegfried, the third instalment of the cycle, Sieglinde’s son (Siegfried) has been raised by Alberich’s brother, the dwarf Mime. For years, the cursed ring has been guarded by Fafner, the dragon. Siegfried uses his immense strength to reforge the shattered fragments of the sword, Nothung. Encouraged by The Wanderer (Wotan in disguise), Siegfried slays the dragon and claims the ring and the magical Tarnhelm (a magical helmet that enables the wearer to change form, and become invisible). Mime attempts to poison Siegfried in order to obtain the ring for himself, and Siegfried kills him. The Wanderer learns from Erda, goddess of the earth, that the era of the gods is waning. Siegfried shatters Wotan’s spear (the symbol of his power) and journeys to the ring of fire where Brünnhilde is sleeping. He bursts through the flames and claims her as his wife, and they fall in love.

The music of Siegfried is perhaps the least well-known of the four operas, although the Forging Song, when Siegfried forges the sword, Nothung, at the end of the First Act, is a known highlight. Wagner’s skill for evoking subterranean atmospheres also comes into play, in the scenes with Fafner. There also is an extraordinary orchestral interlude between the second and third scenes of the Third Act, in which the violins carry a long, extended melodic phrase (an example of Wagner’s unendliche Melodie – the ‘unending melody’). Finally, Brünnhilde's awakening involves a glorious burst of musical sunshine, as she and Siegfried celebrate their love in the face of death ‘Leuchtende Liebe, lachender Tod!’ (‘Radiant love, laughing death!’).

Götterdämmerung

Götterdämmerung sees the final unravelling of the rule of the gods. Deceived by the mortal siblings, Gutrune and Gunther, Siegfried betrays Brünnhilde while under the influence of a memory-suppressing drug. When the truth is ultimately revealed, Brünnhilde returns the ring to the Rhinemaidens, and the era of the gods comes to an end as Valhalla is swallowed in flames. In triumph, she gallops into the fire, where she dies in ecstasy.

- Siegfried (tenor)

- Brünnhilde (high dramatic soprano)

- Gunther (baritone)

- Gutrune (soprano)

- Hagen (bass)

- Alberich (baritone)

- Waltraute (mezzo-soprano)

- First Norn (contralto)

- Second Norn (mezzo-soprano)

- Third Norn (soprano)

- Woglinde (soprano)

- Wellgunde (soprano)

- Flosshilde (mezzo-soprano)

In Götterdämmerung (The Twilight of the Gods), three Norns weave the rope of fate – but it snaps just as they begin to prophesy the end of the era of the gods. Siegfried leaves the ring with Brünnhilde as a token of his devotion, but he is tricked into betraying Brünnhilde by the Gibichung siblings, Gutrune and Gutrune, who ply him with a potion that makes him forget Brünnhilde. Seeing Siegfried wedded to Gutrune, the devastated Brünnhilde reveals Siegfried’s weakness to the devious Gibichung adviser, Hagen, who murders him. When Brünnhilde learns the truth of Siegfried’s deception, she orders a funeral pyre for the fallen hero. As she enters its flames, she bequeaths the ring to the Rhinemaidens and orders Hagen, the demi-god of fire, to set Valhalla, the palace of the gods, aflame. The Rhine overflows its banks, and as the hall of the Gibichungs is consumed by fire and water, the maidens are joyously reunited with the gold, and Valhalla collapses.

The music of Götterdämmerung features several memorable moments, including the heroic tableaux of Siegfried’s Journey Down the Rhine, Siegfried’s Funeral Music, and the climactic, all-encompassing conclusion of the cycle, Brünnhilde’s Immolation, in which we hear the ‘Glorification of Brünnhilde’ theme once again, and the joyful voices of the Rhinemaidens, as the gold is finally restored to them.

Ring cycle in Pop Culture

Literature

- T.S Elliot’s poem The Wasteland references the Ring Cycle and draws from the libretto of Götterdämmerung – including the Rhinemaidens’ call, ‘Weialala leia, Wallala leialala’.

Lord of the Rings

- There is an assumption that the Lord of the Rings is based on the Ring cycle, but JRR Tolkien denied this saying ‘Both rings were round and there the resemblance ceases.’ However, both works are based on the Norse mythology so there is a connection – though Tolkien was not directly inspired by Wagner.

Das Rheingold

- Music from Das Rheingold is featured in Nymphomaniac, directed by Lars von Trier. (For a further operatic connection, the Dogme 95 film Festen, directed by von Trier’s fellow Dogme 95 filmmaker Thomas Vinterberg, was turned into an Olivier Award-winning opera by Mark-Anthony Turnage and Lee Hall by the Royal Ballet and Opera).

- Alien Covenant (2017) features Entry of the Gods into Valhalla in a key scene.

- Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu the Vampyre includes the prelude of Das Rheingold.

Die Walküre

- The orchestral version of Ride of the Valkyries features in many films and TV shows, most famously in Apocalypse Now (1979). The work was also parodied on Loony Tunes in ‘What’s Opera Doc?’

- Ride of the Valkyries is also featured or referenced in Die Hard with a Vengeance (1995), The Blues Brothers (1980), Rango (2011) and Scream (1996)

Siegfried

- Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained was inspired by Siegfried. Django undergoes a similar hero’s journey to Siegfried; his mentor Schultz serves a similar role to Mime, relaying the German legend of Brunhilde and Siegfried to Django in one scene. Django’s wife is named Broomhilda and speaks German. None of Wagner’s music is in the film, but the Dies Irae from Verdi’s Requiem and Beethoven’s Für Elise are both featured. Quentin Tarantino was inspired to adapt the story after seeing a production of Siegfried with Christoph Waltz.

Götterdämmerung

- Bronson (2008) features music from Götterdämmerung and other works in the Ring Cycle

- Army of the Dead (2021) features music from Götterdämmerung

Character List

Gods

- Wotan, King of the Gods (god of light, air and wind) (bass-baritone)

- Fricka, Wotan's wife, goddess of marriage (mezzo-soprano)

- Loge, demigod of fire (tenor)

- Freia, Fricka's sister, goddess of love, youth and beauty (soprano)

- Donner, Fricka's brother, god of thunder (baritone)

- Froh, Fricka's brother, god of spring/happiness (tenor)

- Erda, goddess of wisdom/fate/Earth (contralto)

- The Norns, the weavers of fate, daughters of Erda (contralto, mezzo-soprano, soprano)

Mortals

Wälsungs

- Siegmund, mortal son of Wotan (tenor)

- Sieglinde, his twin sister (soprano)

- Siegfried, their son (tenor)

Neidings

- Hunding, Sieglinde's husband, chief of the Neidings (bass)

Gibichungs

- Gunther, King of the Gibichungs (baritone)

- Gutrune, his sister (soprano)

- Hagen, their half-brother and Alberich's son (bass)

- A male choir of Gibichung vassals and a small female choir of Gibichung women

Valkyries

- Brünnhilde (soprano)

- Gerhilde (soprano)

- Ortlinde (soprano)

- Waltraute (mezzo-soprano)

- Schwertleite (contralto)

- Helmwige (soprano)

- Siegrune (mezzo-soprano)

- Grimgerde (contralto)

- Rossweisse (mezzo-soprano)

Rhinemaidens

- Woglinde (soprano)

- Wellgunde (soprano)

- Flosshilde (mezzo-soprano)

Giants

- Fasolt (bass-baritone/high bass)

- Fafner, his brother, later turned into a dragon (bass)

Nibelungs

- Alberich (bass-baritone)

- Mime, his brother and Siegfried's foster father (tenor)

Other characters

- The Voice of a Woodbird (soprano)

Watch more

Die Walküre

Gods and mortals battle in the second chapter of Wagner’s Ring cycle.

Watch on Stream

Director Barrie Kosky joins forces with conductor Antonio Pappano in a bold new imagining of the first chapter of Wagner's Ring cycle.